Every day, we are exposed to approximately 75,000 artificial chemicals. They’re in the food we eat, the medicines we take, and many of the household products we use. But what do we know about how they affect our bodies?

Not much, it turns out. That’s because toxicology testing is a slow and painstaking process.

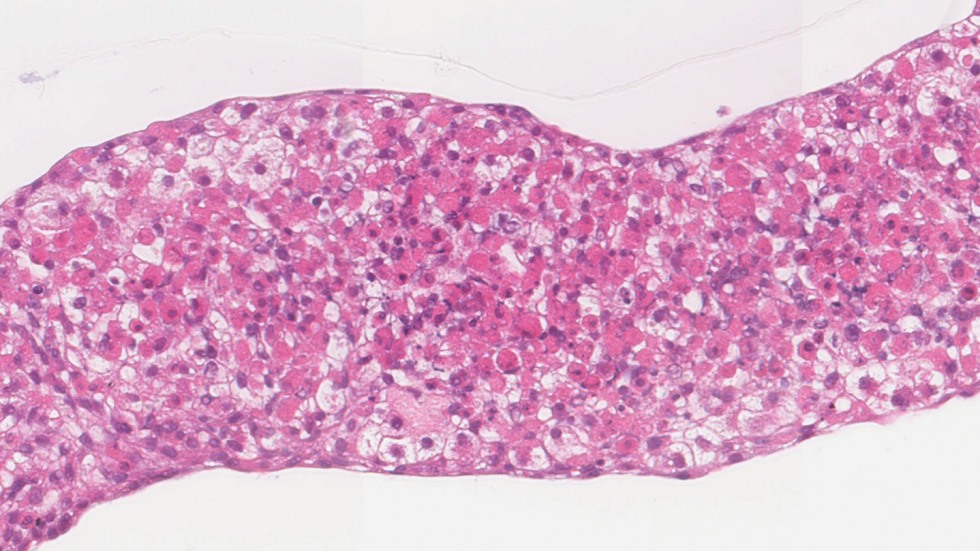

“This kind of research is conducted in mice and rats over a lifetime of the mouse and rat, which is two to three years,” says Kim Boekelheide, professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Brown’s Warren Alpert School of Medicine. “And, it can take up to 10 years to actually get a report.”

Boekelheide says that each time this is done, it can cost approximately $3 million. But even then, scientists can’t be sure that the findings produced from rat and mice tissues are applicable to humans.

“If you expose mice and rats to the same chemical, the tumors you get in mice map to the tumors you get in rats less than half of the time,” he says. “So mice are not predictive of rats and yet we use both of them to predict the human response. I think we can do much better than that.”

Donna McGraw Weiss ’89, a Brown University Trustee, agrees.

“We're developing chemicals all the time and putting them out in the environment,” she says. “When we see some sign that there's a problem, then we go back and do the research once the chemical is already in use.”

McGraw Weiss and her husband Jason, who is involved with animal welfare organizations, thought that Brown would be the perfect place to investigate and promote new ways of performing this kind of science, without the use of animals.

“Our initial investment was actually in a piece of equipment—a high throughput microscope,” she says. “That initial foray into the equipment was like, ‘if we build capacity at Brown, they will come’. There were a number of researchers who said, ‘here's this shared facility at Brown; let me figure out how I can integrate that into my work.’”

And that’s how the idea for Center for Animal Alternatives in Testing (CAAT) at Brown was born.